Mali: Infrastructure

Climate change is expected to significantly affect Mali’s infrastructure sector through extreme weather events, such as flooding and droughts (Figure 12). High precipitation amounts can lead to flooding of roads, while high temperatures can cause roads, bridges and protective structures to develop cracks and degrade more quickly. Transport infrastructure is very vulnerable to extreme weather events, yet essential for social, economic and agricultural livelihoods. Roads serve communities to trade their goods and access healthcare, education, credit as well as other services, especially in rural and remote areas. The absence of railways, seasonal navigability of the Niger River and limited airport facilities increase Mali’s reliance on road transportation. Yet, Mali has one of the lowest road densities in Africa with an average of 38 km / 1 000 km² [24]. Furthermore, only 17 % of Mali’s rural population lives within 2 km of an all-season road, which is 60 % below the African average [24]. Therefore, investments will have to be made into building climate-resilient road networks.

Extreme weather events will also have devastating effects on human settlements and economic production sites, especially in urban areas with high population densities like Bamako or Sikasso. Informal settlements are particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events: Makeshift homes are often built in unstable geographical locations including river banks, where flooding can lead to loss of housing, contamination of water, injury or death. Dwellers usually have low adaptive capacity to respond to such events due to high levels of poverty and a lack of risk-reducing infrastructures. For example, heavy rains in July and August 2018 caused flooding in different regions across Mali, particularly affecting communities along the Niger River including Bamako, Gao, Koulikoro, Mopti, Segou and Timbuktu [25]. A total of 137 000 people were affected (the highest number compared to the previous 6 years), 6 350 houses were destroyed and 2 680 head of cattle were killed [25]. Flooding and droughts will also affect hydropower generation: Mali draws 60 % of its energy from hydropower, with a total installed capacity of 528 MW in 2014 [26]. However, variability in precipitation and climatic conditions could severely disrupt hydropower generation.

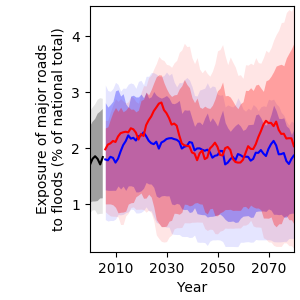

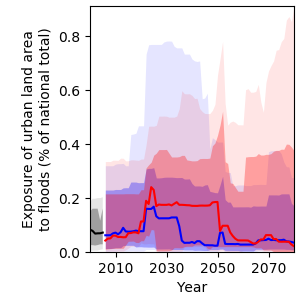

Despite the risk of infrastructure damage being likely to increase due to climate change, precise predictions of the location and the extent of exposure are difficult to make. For example, projections of river flood events are subject to substantial modelling uncertainty, largely due to the uncertainty of future projections of precipitation amounts and their spatial distribution, affecting flood occurrence (see also Figure 4). In the case of Mali, projections for both RCP2.6 and RCP6.0 show almost no change in the exposure of major roads to river floods. In 2000, 1.7 % of major roads were exposed to river floods at least once a year, while by 2080, this value is projected to change to 1.9 % under RCP2.6 and to 2.0 % under RCP6.0. Similarly, exposure of urban land area to river floods is projected to hardly change under either RCP (Figure 13).

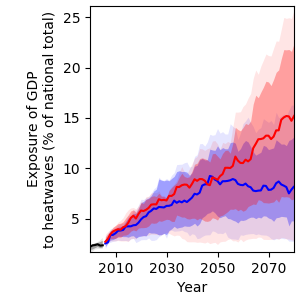

While three of four models project an increase in the exposure of the GDP to heatwaves, the magnitude of the increase is subject to high modelling uncertainty with one model projecting very strong and two models projecting weaker increases (Figure 14). Median model projections for RCP2.6 show an increase from 2.2 % in 2000 to 8.7 % by 2080, whereas under RCP6.0, exposure is projected to increase to 15.2 %. It is recommended that policy planners start identifying heat-sensitive economic production sites and activities, and integrating climate adaptation strategies, such as improved, solar-powered cooling systems, “cool roof” isolation materials or switching the operating hours from day to night [27].

References

[24] C. Briceño-Garmendia, C. Dominguez, and N. Pushak, “Mali’s Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective,” Washington, D.C., 2011.

[25] OCHA, “Humanitarian Bulletin Mali (July-August 2018),” Bamako, Mali, 2018.

[26] UNIDO and ICSHP, “World Small Hydropower Development Report 2016,” Vienna, Austria and Hangzhou, China, 2016.

[27] M. Dabaieh, O. Wanas, M. A. Hegazy, and E. Johansson, “Reducing Cooling Demands in a Hot Dry Climate: A Simulation Study for Non-Insulated Passive Cool Roof Thermal Performance in Residential Buildings,” Energy Build., vol. 89, pp. 142–152, 2015.