Mauritania: Agriculture

Smallholder farmers in Mauritania are increasingly challenged by the uncertainty and variability of weather caused by climate change [16], [17]. Since crops are predominantly rainfed, yields highly depend on water availability from precipitation and are prone to drought. However, the length and intensity of the rainy season is becoming increasingly unpredictable and the use of irrigation facilities remains limited: In 2004, less than 10 % of the estimated irrigation potential of 250 000 ha (0.6 % of total national crop land) were irrigated [6]. The main irrigated crop is rice, in addition to maize, sorghum and vegetables [22]. Especially in central and northern Mauritania, soils are sandy and poor in nutrients, which complicates irrigation and crop production [22].

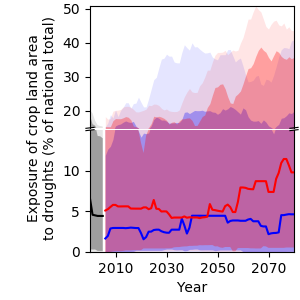

Crop land exposure to drought

Currently, the high uncertainty of projections regarding water availability (Figure 10) translates into high uncertainty of drought projections (Figure 11). According to the median over all models employed for this analysis, the national crop land area exposed to at least one drought per year will increase from 6 % in 2000 to 10 % in 2080 under RCP6.0 and decrease to 5 % under RCP2.6. Under RCP6.0, the likely range of drought exposure of the national crop land area per year widens from 0.3–19 % in 2000 to 0.6–36 % in 2080. The very likely range widens from 0–20 % in 2000 to 0.01–44 % in 2080. This means that some models project a doubling of drought exposure over this time period, while others project no change.

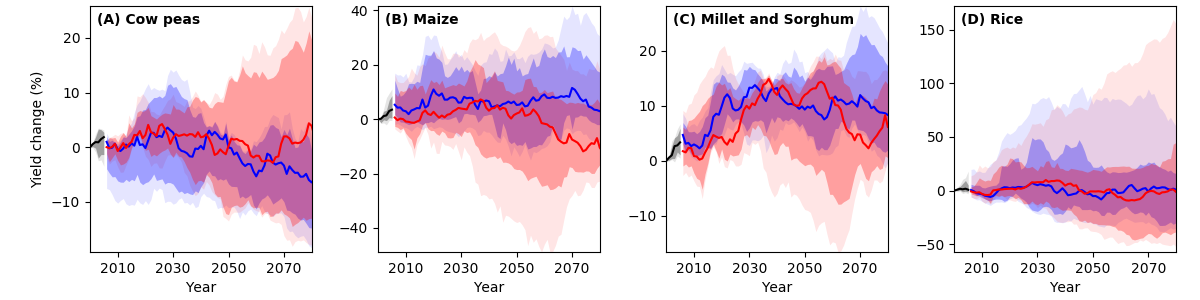

Crop yield projections

In terms of yield projections, model results indicate high uncertainty (Figure 12)6. Compared to the year 2000, yields of cow peas are projected to decrease by 6 % under RCP2.6 and increase by 4 % under RCP6.0. A possible explanation for the positive results under RCP6.0 is that cow peas are so-called C3 plants, which follow a different metabolic pathway than maize, millet and sorghum (C4 plants), and benefit more from the CO2 fertilisation effect under higher concentration pathways. For maize, the trend is reversed: Under RCP2.6, yields are projected to slightly increase by 3 % and decrease by 11 % under RCP6.0. Millet and sorghum are projected to gain 8 % under RCP2.6 and 6 % under RCP6.0. The higher increases under RCP2.6 can be explained by higher precipitation projections under RCP2.6 (Figure 5). Finally, yields of rice are projected to not change under either RCP, however, some models project an increase of up to 200 %. Although some yield changes may appear small at the national level, they will likely increase more strongly in some areas and, conversely, decrease more strongly in other areas as a result of climate change impacts.

Overall, adaptation strategies such as switching to improved varieties in climate change-sensitive crops need to be considered, yet should be carefully weighed against adverse outcomes, such as a resulting decline of agro-biodiversity and loss of local crop types.

6 Modelling data is available for a selected number of crops only. Hence, the crops listed on page 2 may differ. Maize, millet and sorghum are modelled for all countries, except for Madagascar.

References

[6] FAO, “AQUASTAT Database.” Online available: http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/data/query/index.html?lang=en [Accessed: 07-May-2020].

[16] K. Sissoko, H. van Keulen, J. Verhagen, V. Tekken, and A. Battaglini, “Agriculture, Livelihoods and Climate Change in the West African Sahel,” Reg. Environ. Chang., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 119–125, 2011.

[17] P. Ozer, Y. C. Hountondji, J. Gassani, B. Djaby, and D. L. F, “Évolution récente des extrêmes pluviométriques en Mauritanie (1933–2010),” XXVIIeme Colloq. l’Association Int. Climatol., pp. 394–400, 2014.

[22] Y. M. Bachir and A. Ould Hamadi Sherif, “Mauritania Livelihood Zoning Plus,” Washington, D.C. and Madrid, Spain, 2013.