Climate change threatens the health and sanitation sector through more frequent incidences of heatwaves, floods, droughts and storms, including cyclones. Among the key health challenges in Madagascar are morbidity and mortality through vector-borne diseases such as malaria, waterborne diseases related to extreme weather events (e.g. flooding) such as diarrhoea, respiratory diseases, tuberculosis and HIV [32]. Climate change also impacts food and water supply, thereby increasing the risk of malnutrition, hunger and death by famine. Many of these challenges are expected to become more severe under climate change. According to the World Health Organization, Madagascar recorded an estimated 2.2 million cases of malaria including 5 350 deaths in 2018 [33]. Climate change is likely to have an impact on the geographic range of vector-borne diseases: In Madagascar, malaria usually does not occur above 1 500 m [34]. However, temperature increases could expand occurrence to higher-lying areas. This is already the case in Antananarivo which used to be largely free of malaria but is now observing rising numbers of cases [35]. Malaria is also likely to increase in many parts of Madagascar due to flooding and stagnant waters, which provide a breeding ground for mosquitos [35]. Climate change also poses a threat to food security and malnutrition, particularly for subsistence farmers. Chronic malnutrition is generally high with 42 % and could further increase due to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic [36]. Furthermore, access to healthcare is often complicated in Madagascar: 40 % of the population live in areas far away from health centers and have to travel for hours to seek medical treatment [35]. Access is even more difficult in the rainy season when many rural areas are cut off by impassable roads.

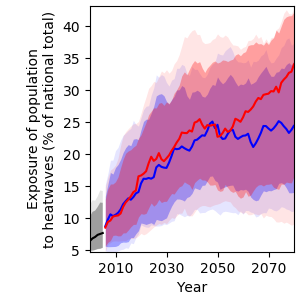

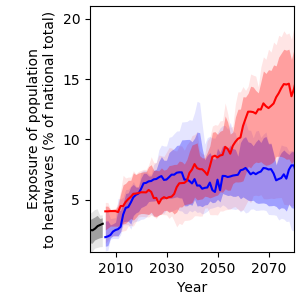

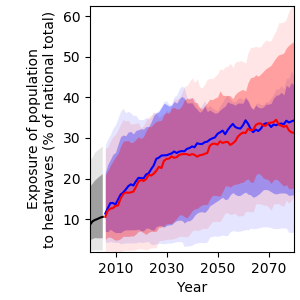

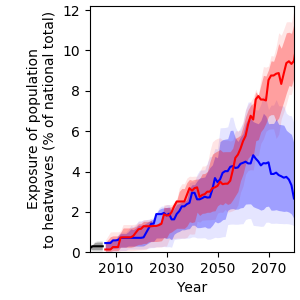

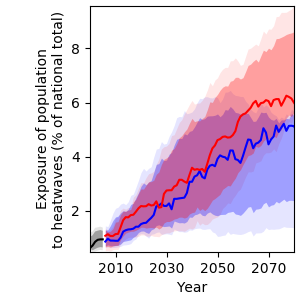

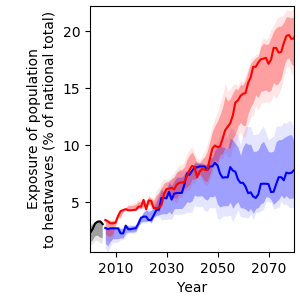

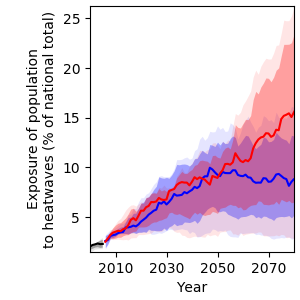

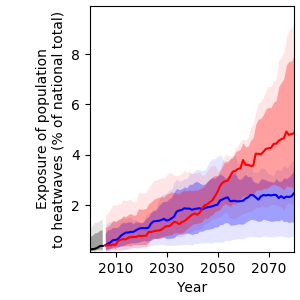

Exposure to heatwaves

Rising temperatures will result in more frequent heatwaves in Madagascar, leading to increased heat-related mortality. Under RCP6.0, the population affected by at least one heatwave per year is projected to increase from 0.2 % in 2000 to 4.8 % in 2080 (Figure 18).

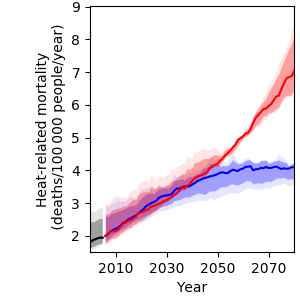

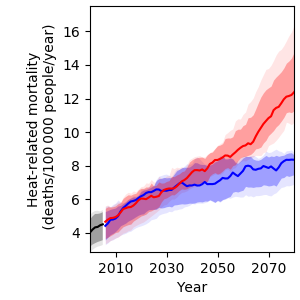

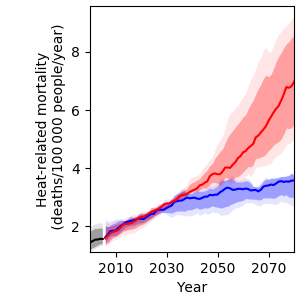

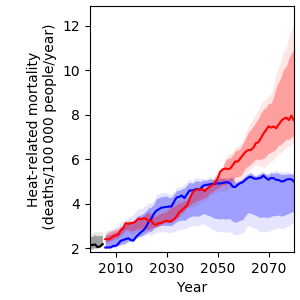

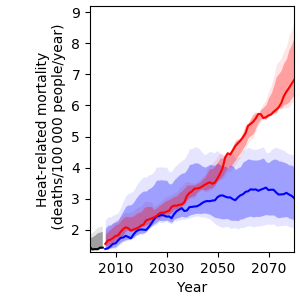

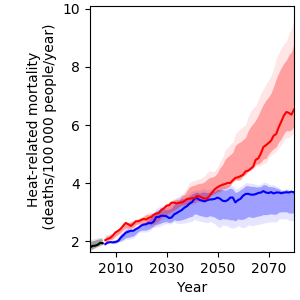

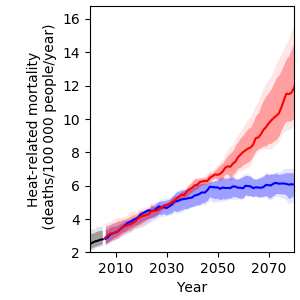

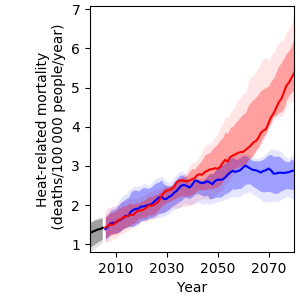

Heat-related mortality

Furthermore, under RCP6.0, heat-related mortality will likely increase from 1.3 to 5.4 deaths per 100 000 people per year by 2080. This translates to an increase by a factor of more than four towards the end of the century compared to year 2000 levels, provided that no adaptation to hotter conditions will take place (Figure 19). Under RCP2.6, heat-related mortality is projected to increase to 2.9 deaths per 100 000 people per year in 2080.

References

[32] Ministère de la Santé Publique Madagascar, “Politique nationale de santé,” Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2016.

[33] WHO, “World Malaria Report 2019,” Rome, Italy, 2019.

[34] U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, “Madagascar: Malaria Operational Plan FY 2017,” Washington, D.C., 2017.

[35] S. Barmania, “Madagascar’s Health Challenges,” Lancet, vol. 386, pp. 729–730, 2015.

[36] WFP, “Madagascar Country Brief August 2020,” Rome, Italy, 2020.