Over the last decades, Mali has experienced strong seasonal and annual variations in precipitation, which present a major constraint to agricultural production [16], [17]. Mali was hit by severe droughts between 1970 and 2000 as a result of declining levels of precipitation since the mid-1950s. Although precipitation levels recovered towards the year 2000, they have remained below the national average of the past century [18]. The 2012 Sahel drought affected a total of 4.6 million people in Mali [19]. Extreme droughts tend to have a cascading effect: First, lack of water reduces crop yields, which increases the risk of food insecurity for people and their livestock, which in turn limits their capacity to cope with future droughts. Transhumance used to be an effective way to deal with variations in precipitation and droughts in Mali. However, people’s reliance on this type of pastoralism has been challenged by increasingly unpredictable precipitation patterns. The resulting lack of pastures and water has led to increasing competition over these scarce resources, particularly along the Niger River and in the Inner Niger Delta. Other factors complicating transhumance include poor natural resource management, population growth, conflicts between farmers and herders and terrorist activities in the greater region, making this mode of living less profitable and sometimes even dangerous [20].

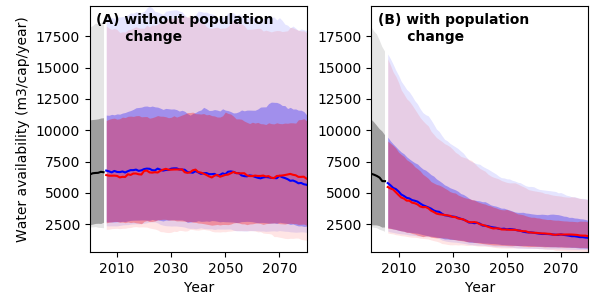

Per capita water availability

Current projections of water availability in Mali display high uncertainty under both GHG emissions scenarios. Assuming a constant population level, multi-model median projections suggest only slight decreases in water availability over Mali by the end of the century under both emissions scenarios (Figure 8A). Yet, when accounting for population growth according to SSP2 projections5, per capita water availability for Mali is projected to decline by 77 % by 2080 relative to the year 2000 under both scenarios (Figure 8B). While this decline is primarily driven by population growth, rather than climate change, it highlights the great urgency to invest in water saving measures and technologies for future water consumption.

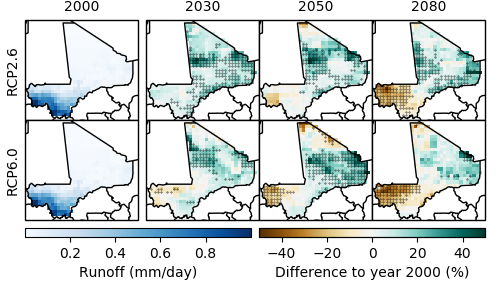

Spatial distribution of water availability

Projections of future water availability from precipitation vary depending on the region and scenario (Figure 9). In line with precipitation projections, water availability is projected to decline by 20 % in the south-west of Mali by 2080 under both RCPs. In the northern half of the country, however, water availability is projected to increase by 15 % under RCP2.6. Under RCP6.0, model agreement on these increases is low towards the end of the century. This modelling uncertainty, along with the high natural variability of precipitation, contributes to uncertain future water availability in particular in the north of Mali.

5 Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSPs) outline a narrative of potential global futures, including estimates of broad characteristics such as country level population, GDP or rate of urbanisation. Five different SSPs outline future realities according to a combination of high and low future socio-economic challenges for mitigation and adaptation. SSP2 represents the “middle of the road”-pathway.

References

[16] B. Traore, M. Corbeels, M. T. van Wijk, M. C. Rufino, and K. E. Giller, “Effects of Climate Variability and Climate Change on Crop Production in Southern Mali,” Eur. J. Agron., vol. 49, pp. 115–125, 2013.

[17] B. Sultan, P. Roudier, P. Quirion, A. Alhassane, B. Muller, M. Dingkuhn, P. Ciais, M. Guimberteau, S. Traore, and C. Baron, “Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Sorghum and Millet Yields in the Sudanian and Sahelian Savannas of West Africa,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 8, pp. 1–9, 2013.

[18] USAID, “A Climate Trend Analysis of Mali,” Washington, D.C., 2012.

[19] World Bank, “Sahel Drought Situation Report No. 9: Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal,” Washington, D.C., 2012.

[20] UNOWAS, “Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel,” n.p., 2018.