One option to help farmers increase the productivity of soil, water, nutrients and other resources is the genetic improvement of crops under stress and optimal growing conditions (IPCC, 2019; Searchinger et al., 2014; Voss-Fels et al., 2019). An improved or modern variety is a new variety of a plant species which produces higher yields, higher quality or provides better resistance to plant pests and diseases, while minimizing the pressure on the natural environment (Access to Seeds Index, 2020). Such modern varieties are genetically uniform, which means that their characteristics are constant within all individuals of that specific variety. The exact definition and requirements of improved varieties depend on a country’s legislation and international treaties (e.g. harmonized Seed Regulation adopted by ECOWAS). Improved varieties have, for example, higher tolerances to abiotic stressors, such as drought (Fisher et al., 2015), resistances to biotic stressors (e.g. diseases and pests), improved resource use or other changes that permit altering the agronomic management by, for example, needing shorter growing cycles. Along with labour saving technologies and flexible credits, locally adapted seed varieties are among the most needed inputs for farmers in Burkina Faso (Roncoli et al., 2001).

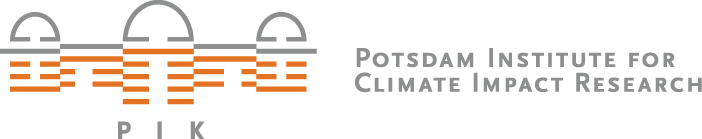

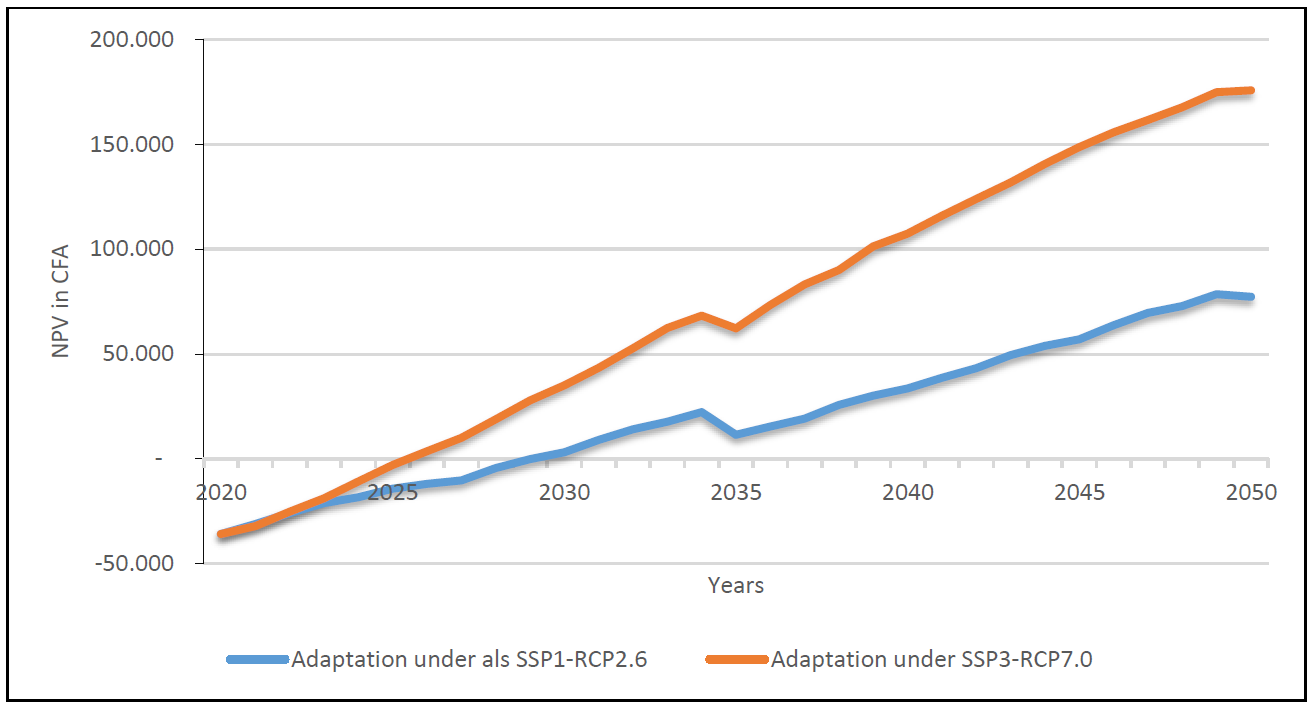

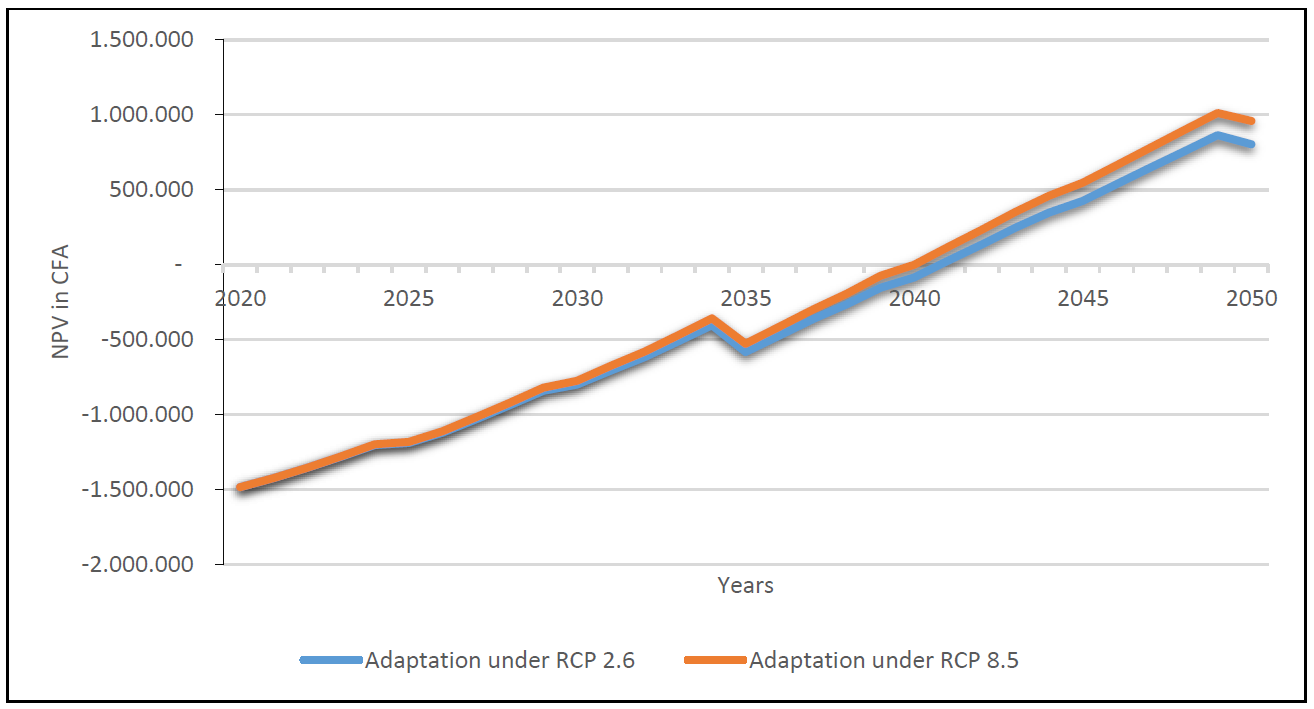

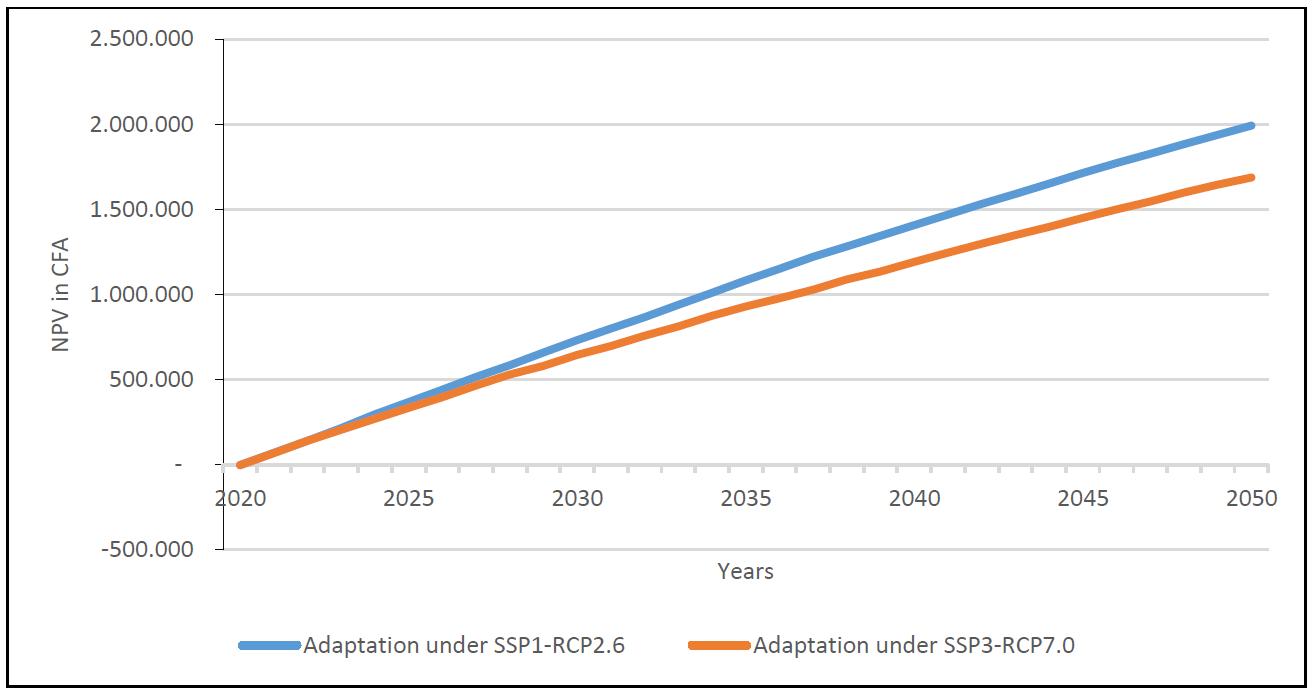

Improved crop varieties are a highly beneficial adaptation strategy in Burkina Faso. Furthermore, the cost-benefit analysis shows a very positive return on a rather small-scale investment (see Figure 1). Due to its positive impact on yield increase and stability as well as increased levels of nutrients, improved varieties can also help to decrease malnutrition and undernutrition. However, there are several factors, such as high prices of agricultural inputs, the insufficiency of logistical and financial support, the poor organization of the sector, the lack of motivation by seed producers to enter the market, the climatic risks associated with agricultural production and a decline in soil fertility, which impede the use of improved seeds by farmers. Besides that, insufficient agronomic knowledge or non-locally adapted varieties can lead to controversial effects and negative outcomes of this strategy.

To achieve the optimal adaptation effect of improved varieties, the following recommendations should be considered:

- Ideally, improved varieties are promoted that fulfil several conditions, such as farmers’ preferences, local suitability, agronomic management and that are available and accessible for smallholder farmers. The sufficient supply of locally adapted good quality seeds on the local level should be, therefore, supported.

- To promote a continuing process of innovation adoption, efforts should be directed to creating a seed sector that covers the overall process for improved seeds from plant breeding and pre-breeding to seed propagation, marketing and advisory, whilst focusing on farmers’ needs.

- Knowledge transfer regarding the varieties’ potential and the best way to cultivate them can help farmers to use improved varieties.

- For a profitable adoption it is necessary to ameliorate the functioning of the agricultural value chain including functioning infrastructure and agriculture markets to make agricultural inputs available and accessible.

- It is also important to highlight the value of local landraces, as they are a pillar for safeguarding local traditions, agronomic practices and accompanying knowledge. Such a safeguarding of seeds and practices could be institutionalized by in-situ conservation projects, local seed banks, corporations with national or international gene banks and diversity fairs.

- A better communication and interaction of seed sector stakeholders can help to improve seed and knowledge dissemination on a local, regional and national level.

References

- Access to Seeds Index. (2020). Definitions. https://www.accesstoseeds.org/definitions/

- Fisher, M., Abate, T., Lunduka, R. W., Asnake, W., Alemayehu, Y., & Madulu, R. B. (2015). Drought tolerant maize for farmer adaptation to drought in sub-Saharan Africa: Determinants of adoption in eastern and southern Africa. Climate Change, 133(2), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1459-2

- IPCC. (2019). Climate Change and Land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Ishikawa, H., Drabo, I., Joseph, B., Batieno, B., Muranaka, S., Fatokoun, C., & Boukar, O. (2020). Characteristics of farmers’ selection criteria for cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) varieties differ between north and south regions of Burkina Faso. Ex. Agric, 56(1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1017/S001447971900019X

- Roncoli, C., Ingram, K., & Kirshen, P. (2001). (2001): The costs and risks of coping with drought: Livelihood impacts and farmers’ responses in Burkina Faso. Clim. Res., 19, 119–132. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr019119

- Searchinger, T., Hanson, C., & Lacape, J.-M. (2014). Crop Breeding: Renewing the Global Commitment. WRI.

- Voss-Fels, K. P., Stahl, A., Wittkop, B., Lichthardt, C., Nagler, S., Rose, T., Chen, T.-W., Zetzsche, H., Seddig, S., Baig, M. M., Ballvora, A., Frisch, M., Ross, E., Hayes, B. J., Hayden, M. J., Ordon, F., Leon, J., Kage, H., Friedt, W., … Snowdon, R. J. (2019). Breeding improves wheat productivity under contrasting agrochemical input levels. Nature Plants, 5(7), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0445-5